Nuestros ancestros en marcha: Ambulación de “Lucy” Austrolopithecus afarensis … es develada por la ciencia.

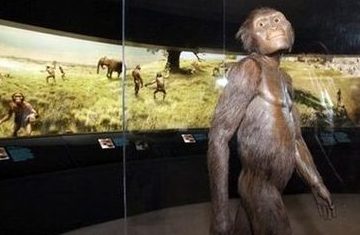

Sabemos de “Lucy”, un remoto ancestro nuestro, muchas cosas. Era hembra de Austrolopithecus afarensis, tiene 3,2 millones de años de antigüedad, a fascinado a los científicos, que han intentado desentrañar los detalles de su vida como si se tratara de una estrella de cine. Sabemos que “Lucy” medía alrededor de un metro y pesaba unos 27 kilos, que fue madre y que llegó a los 20 años de edad. También se sospechaban que caminaba erguida, pero un nuevo estudio, publicado esta semana en la revista Science, viene a confirmarlo. La vieja Lucy y sus congéneres tenían unos pies muy similares a los nuestros, rígidos y arqueados.

El pie casi humano de Lucy

Judith de Jorge

El cuarto metatarso del Australopithecus afarensis. Carol Ward/University of Missouri

Madrid, España, 13 de febrero de 2011, ABC.- Desde que su esqueleto fue descubierto en Etiopía, Lucy, una hembra de Austrolopithecus afarensis de 3,2 millones de años de antigüedad, ha sido uno los ancestros humanos más fascinantes para los científicos, que han intentado desentrañar los detalles de su vida como si se tratara de una estrella de cine.

Sabemos de ella muchas cosas. Que medía alrededor de un metro y pesaba unos 27 kilos, que fue madre y que llegó a los 20 años de edad. También sospechaban que caminaba erguida, pero un nuevo estudio, publicado esta semana en la revista Science, viene a confirmarlo. La vieja Lucy y sus congéneres tenían unos pies muy similares a los nuestros, rígidos y arqueados. Este descubrimiento apoya la hipótesis de que el Austrolopithecus afarensis caminaba principalmente erguido, en vez de moverse a través de los árboles.

El Austrolopithecus afarensis vivió hace entre 3,7 y 2,9 millones de años y su más famoso espécimen es Lucy, cuyo esqueleto parcial reveló que caminaba erguida como lo hacemos nosotros. Los investigadores han mantenido un gran debate sobre en qué medida Lucy y sus congéneres eran bípedos, sin embargo, su conocimiento se veía frenado por los escasos registros fósiles de huesos clave del pie de estos individuos. Ahora, científicos de la Universidad de Missouri en Columbia (Estados Unidos), dirigidos por Carol Ward, describen un nuevo hueso de pie de la especie procedente de Hadar, en Etiopía, en un famoso yacimiento. El hueso, un cuarto metatarso, está casi perfectamente conservado. Aporta evidencias de los arcos y de que su propietario podía soportar un estilo de locomoción humano.

Arco bien formado

El hueso tiene varias características similares a las del pie de los humanos modernos. Los pies de los seres humanos, únicos entre los primates, tienen dos arcos, longitudinal y transversal. Durante la locomoción bípeda, estos arcos realizan dos funciones fundamentales: hacer de palanca cuando el pie se levanta del suelo y absorber el choque cuando la planta del pie se encuentra con el suelo al final de la zancada. Los pies de los monos no tienen arcos permanentes, son más flexibles que los pies humanos y tienen un dedo gordo con una gran movilidad, atributos importantes para escalar y agarrarse a los árboles. Ninguno de estos rasgos simiescos están presentes en el pie de A. afarensis.

Este pie, con su arco bien formado, debió de haber sido lo suficientemente duro para presionar contra el suelo pero también lo suficientemente flexible para absorber choques. Por ello, el fósil sugiere que los pies del A. afarensis se habían transformado por completo de estructuras de agarre a otras que facilitaban el caminar similar a los humanos y la carrera sobre dos pies. Así que, como ya se sospechaba, Lucy caminaba, más o menos, como cualquier mujer actual.

Pies como los nuestros permitían a Lucy caminar erguida

Foto: Gerbil/Wokimedia Commons

Madrid, España, 11 de febrero de 2011, Europa Press.- Un hueso del pie del ‘Australopithecus afarensis’, un familiar de los primeros humanos, sugiere que estos homínidos tenían píes rígidos y arqueados, como los actuales humanos, según un estudio de la Universidad de Missouri en Columbia (Estados Unidos) que se publica en la revista ‘Science’.

Estos descubrimientos apoyan la hipótesis de que el ‘A. afarensis’ caminó principalmente erguido, en vez de ser una criatura más versátil que también se moviera a través de los árboles. El ‘A. afarensis’ vivió hace entre 3,7 y 2,9 millones de años y su más famoso espécimen es ‘Lucy’, cuyo esqueleto parcial reveló que caminaba erguida.

Los investigadores han mantenido un gran debate sobre en qué medida el ‘A. afarensis’ era un bípedo, sin embargo, su conocimiento se ha visto frenado por los escasos registros fósiles de huesos clave del pie del ‘A. afarensis’.

Los científicos, dirigidos por Carol Ward, describen ahora un nuevo hueso de pie de la especie procedente de Hadar, en Etiopia, que señalan está casi perfectamente conservado. El hueso tiene varias características similares a las del pie de los humanos modernos, en oposición a las de otros simios. Por ejemplo, sus dos terminaciones presentan formas circulares opuestas entre sí y el pie muestra además un ángulo relativamente brusco desde la base del pie al dedo principal.

Este pie, con su arco bien formado, debió haber sido lo suficientemente duro para presionar contra el suelo pero también lo suficientemente flexible para absorber choques. Este fósil por ello sugiere que los pies del ‘A. afarensis’ se habían transformado por completo de estructuras de agarre a otras que facilitaban el caminar similar a los humanos y la carrera sobre dos pies.

————————————————————————

Discoverers of a partial, 3.6-million-year-old skeleton from Lucy’s species say that it unveils a surprisingly humanlike walking ability, although not everyone agrees.

Credit: Y. Haile Selassie et al./PNAS 2010

Big Man’s skeleton was discovered in a part of the Afar region of Ethiopia called Woranso-Mille, about 48 kilomteres north of the spot where Lucy was found.

————————————————————————-

A tiny 3.2-million-year-old fossil found in East Africa gives Lucy’s kind an unprecedented toehold on humanlike walking.

Australopithecus afarensis, an ancient hominid species best known for a partial female skeleton called Lucy, had stiff foot arches like those of people today, say anthropologist Carol Ward of the University of Missouri in Columbia and her colleagues. A bone from the fourth toe — the first such A. afarensis fossil unearthed — provides crucial evidence that bends in this species’ feet supported and cushioned a two-legged stride, the scientists report in the Feb. 11 Science.

“We now have the evidence we’ve been lacking that A. afarensis had fully developed, permanent arches in its feet,” Ward says. Survival for Lucy and her comrades must have hinged on abandoning trees for a ground-based lifestyle, she proposes.

The new fossil confirms that members of Lucy’s species could have made 3.6-million-year-old footprints previously found in hardened volcanic ash at Laetoli, Tanzania (SN Online: 3/22/10), she says. A. afarensis lived from about 4 million to 3 million years ago.

Scientists have argued for more than 30 years about whether Lucy and her kin mainly strode across the landscape or split time between walking and tree climbing.

News of arched feet in these hominids comes on the heels of a report that a recently discovered A. afarensis skeleton, dubbed Big Man, displays long legs, a relatively narrow chest and an inwardly curving back, signs of a nearly humanlike gait (SN: 7/17/10, p. 5).

“There were far too many highly detailed adaptations in every part of the A. afarensis skeleton for upright walking and exclusive ground travel not to have emerged,” remarks anthropologist Owen Lovejoy of Kent State University in Ohio, who studied Big Man’s remains.

A foot much like that attributed to Lucy’s kind by Ward’s group had already evolved by 4.4 million years ago in the early hominid Ardipithecus (SN: 1/16/10, p. 22), Lovejoy says. Although Ardipithecus had an opposable big toe incapable of propelling a two-legged gait, this creature walked effectively using its other toes, in his view.

Based on the new find, A. afarensis does appear to have had arched feet, remarks anthropologist William Jungers of Stony Brook University School of Medicine in New York. But other foot features, including long, curved fifth toes, indicate that a skeletal system for upright walking had not fully evolved in Lucy’s kind, Jungers asserts.

Considerable differences in foot anatomy may have existed among members of A. afarensis, Jungers says. An analysis of fossil ankle bones published in 2010 by other researchers concluded that Lucy had flat feet while many of her comrades had an arch at the back of the foot.

“Even if Lucy had lower arches than other individuals, she still would have had the stiff, humanlike foot structure that we see in people but not in apes,” Ward says.

Excavations at one of several sites at Hadar, Ethiopia, yielded the ancient toe bone in 2000. Since 1975, this location has produced more than 250 fossils representing at least 17 A. afarensis individuals.

Shape and design features of the fossil toe closely match those of corresponding toes on people but not chimpanzees or gorillas, Ward’s team says.

————–

http://www.sciencenews.org/view/access/id/60468/title/bb_bones_vertical.jpg

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Rivers in the sky: Atmospheric bands of water vapor can cause flooding and extreme weather

- Cerebral Delights: The amygdala, a part of the brain known for its role in fear, also helps people spot rewards — and go after them

- Brain Boosters: Some nutritional supplements provide real food for thought

An older guy has sauntered into Lucy’s life, and some researchers believe he stands ready to recast much of what scientists know about the celebrated early hominid and her species.

Excavations in Ethiopia’s Afar region have uncovered a 3.6-million-year-old partial male skeleton of the species Australopithecus afarensis. This is the first time since the excavation of Lucy in 1974 that paleoanthropologists have turned up more than isolated pieces of an adult from the species, which lived in East Africa from about 4 million to 3 million years ago.

A nearly complete skeleton of an A. afarensis child has been retrieved from another Ethiopian site (SN: 9/23/06, p. 195).

Discoverers of the skeleton, led by anthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, consider this a Desi Arnaz moment. As the late actor often exclaimed on his classic television show, “Lucy, you got some ’splainin’ to do!” But other researchers are not so convinced that the new fossil changes much of what they already knew about Lucy and her kind.

Haile-Selassie’s team has dubbed its new find Kadanuumuu, which means “big man” in the Afar language. At an estimated 5 to 5½ feet tall, he would have towered over 3½-foot-tall Lucy. Excavations between 2005 and 2008 in a part of Afar called Woranso-Mille — about 48 kilometers north of where Lucy’s 3.2-million-year-old remains were found — yielded fossils from 32 bones of the same individual.

Big Man’s long legs, relatively narrow chest and inwardly curving back denote a nearly humanlike gait and ground-based lifestyle, according to a preliminary report published online June 21 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Lucy has often been portrayed as having had a fairly primitive two-legged gait and a penchant for tree climbing.

Big Man’s humanlike shoulder blade differs as much from those of chimpanzees as it does from those of gorillas, Haile-Selassie says. The shape of that bone, combined with characteristics of five recovered ribs, suggest to Haile-Selassie’s team that Big Man’s chest had a humanlike shape. Earlier reconstructions of Lucy’s rib cage had endowed her with a chimplike, funnel-shaped chest.

So despite chimps’ close genetic relationship to people, he says, this new fossil evidence supports the view that chimps have evolved a great deal since diverging from a common human-chimp ancestor roughly 7 million years ago and are not good models for ancient hominids.

Big Man’s shoulder blade bolsters recent analyses of 4.4-million-year-old Ardipithecus ramidus that also challenge traditional views of ancient hominids as chimplike (SN: 1/16/10, p. 22).

Estimates of Lucy’s build were based on comparisons to chimps and indicated to some scientists that she lacked the easy, straight-legged stride of people today. Haile-Selassie and his colleagues suspect that their final reconstruction of Big Man’s anatomy will provide a better model for assessing what Lucy looked like.

“Whatever we’ve been saying about afarensis based on Lucy was mostly wrong,” Haile-Selassie says. “The skeletal framework to enable efficient two-legged walking was established by the time her species had evolved.”

Lucy’s legs were short because of her small size, he adds. If Lucy had been as large as Big Man, her legs would have nearly equaled his in length, Haile-Selassie estimates.

Although lacking a skull and teeth, Big Man preserves most of the same skeletal parts as Lucy, as well as a nearly complete shoulder blade and a substantial part of the rib cage.

“This beautiful afarensis specimen confirms the unique skeletal shape of this species at a larger size than Lucy, in what appears to be a male,” remarks anthropologist Carol Ward of the University of Missouri in Columbia.

A long-standing debate over how well Lucy’s kind walked and whether they spent much time in the trees appears unlikely to abate as a result of Big Man’s discovery, though. “There’s nothing special I can see on this new find that will change anyone’s opinion” on how the species navigated the landscape, comments Harvard University anthropologist Daniel Lieberman.

Haile-Selassie’s team disagrees. Big Man demonstrates that A. afarensis spent most of the time on the ground, the researchers conclude.

“They were good walkers, but we don’t know how well they ran,” Haile-Selassie says. Big Man’s long-legged stride indicates that members of his species could have made 3.6-million-year-old footprints found more than 30 years ago at Laetoli, Tanzania (SN Online: 3/22/10),

Anthropologist Owen Lovejoy of Kent State University in Ohio, a coauthor of the new paper, regards Big Man as having been an “excellent runner.” His pelvis supported humanlike hamstring muscles and, as indicated by the Laetoli footprints, his feet had arches, Lovejoy holds.

Fossil hominid skeletons as complete as Big Man “are few and far between,” says anthropologist William Jungers of Stony Brook University in New York. But the new find mostly confirms what was already known about Lucy, he asserts. Lucy’s kind, including Big Man, were decent tree climbers, even if they couldn’t hang from branches or swing from limb to limb as chimpanzees do, he says.

“Riddle me this,” asks Jungers in considering Hailie-Selassie’s emphasis on a ground-dwelling A. afarensis. “Where did they sleep? Did they wait for fruit to fall to the ground? Where did they go to escape predators?”

Groups of A. afarensis individuals must have devised ground-based strategies to ward off predators, Lovejoy responds. Some big cats would have negotiated trees better than Lucy’s kind, he notes.

Jungers also doubts Lovejoy and Haile-Selassie’s contention that a nearly humanlike gait had evolved in A. afarensis. Big Man includes only one nearly complete limb bone, from the lower left leg, which makes it difficult to estimate how long his legs were relative to his arms, Jungers contends.

Limb remains of hominid species that came after afarensis indicate that they evolved increasingly longer legs and a more efficient walking stance, Jungers adds.

In his view, hips conducive to walking slowly with legs wide apart evolved in an even earlier hominid, 6-million-year-old Orrorin tugenensis (SN: 3/29/08, p. 205)

] and characterized later Australopithecus species, including Lucy’s kind.

Haile-Selassie counters that features of Big Man’s pelvis related to walking closely resemble those of a 1.4-million to 900,000-year-old female Homo erectus from another Ethiopian site (SN: 12/6/08, p. 14).

Big Man’s legs also demonstrate that the comparably long legs of nearly 2-million-year-old South African hominids don’t represent a transition to the Homo genus (SN: 5/8/10, p. 14), Haile-Selassie asserts.

Haile-Selassie doubts that additional pieces of Big Man’s skeleton will turn up. “If anything more was there, we would have found it by now,” he says with a resigned laugh.

Back story: Fragmentary evidence

—

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.contrainjerencia.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2014%2F07%2Ftimthumb.php_1.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.radio36.com.uy%2Fentrevistas%2F2014%2F08%2F01%2Fclip_image002_0546.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.radio36.com.uy%2Fentrevistas%2F2014%2F08%2F01%2Fclip_image002_0545.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fimg.youtube.com%2Fvi%2FIq04dnHwpYc%2F0.jpg)